Impossibly, we’re near the end of the year. I’m not sure I swam once this summer, and yet the trees are poking their bones at the sky, at me, making some kind of accusation about time. See? Nature seems to say. Time is going to happen, and it did.

As if I needed more evidence, I just taught holiday baking class at Honest Weight Food Co-op. When I wrote the class description, I thought it would be fun to explore savory shortbread, and it was. Seeking advice on Instagram, lots of people recommended cheese as the springboard. I resisted that because I wanted to keep my explorations in the flour flavors — of course — and thought that cheese would overwhelm the wild tastes I want to highlight.

The first batch I made was really not tasty. I skipped all the sugar and ended up with super pale crumbs. Back to the drawing board! After reading a million online recipes – including my own, which I’d forgotten I wrote for Edible Brooklyn, as a holiday baking guide – and flipping through the SISTER PIE cookbook, Dorie Greenspan’s BAKING: FROM MY HOME TO YOURS, the new TARTINE, and the new JOY OF COOKING, I came up with some guidelines for playing the game of savory shortbread.

TEMPLATE RECIPE

1 stick/4 ounces/113 g soft butter, cubed

3 tablespoons/45 g sugar

1 ¼ cups/ 130-145 g whole grain flour (whole grain flours weigh differently, which is why there is a range in grams, but not cups)

½ teaspoon salt

About ½ to 1 teaspoon of dried herbs or spices

Cream together butter and sugar. Whisk flour, salt and spices together in a separate bowl. Combine the flour mixture with the creamed butter & sugar. You may need to add a little more flour, or a little liquid. You are going for a stiff dough, but if the mixture is too crumby, add a teaspoon of water or maybe some alcohol to pull it all together.

Roll the dough flat between sheets of waxed paper, ¼ inch thick. Alternately, use the waxed paper wrapper from the butter to roll some dough into a round or square log that you will slice into shortbreads.

Now is the time to sprinkle some nigella seeds, or pepper flakes, or herbs de Provence and salt, pressing the additions lightly into the square with your rolling pin. If you’ve made rolls, you can press these tasty things onto the sides. Refrigerate the dough on a cookie sheet for a couple of hours or a couple of days. OR, if you are short on time, flash in the freezer for about 20-30 minutes.

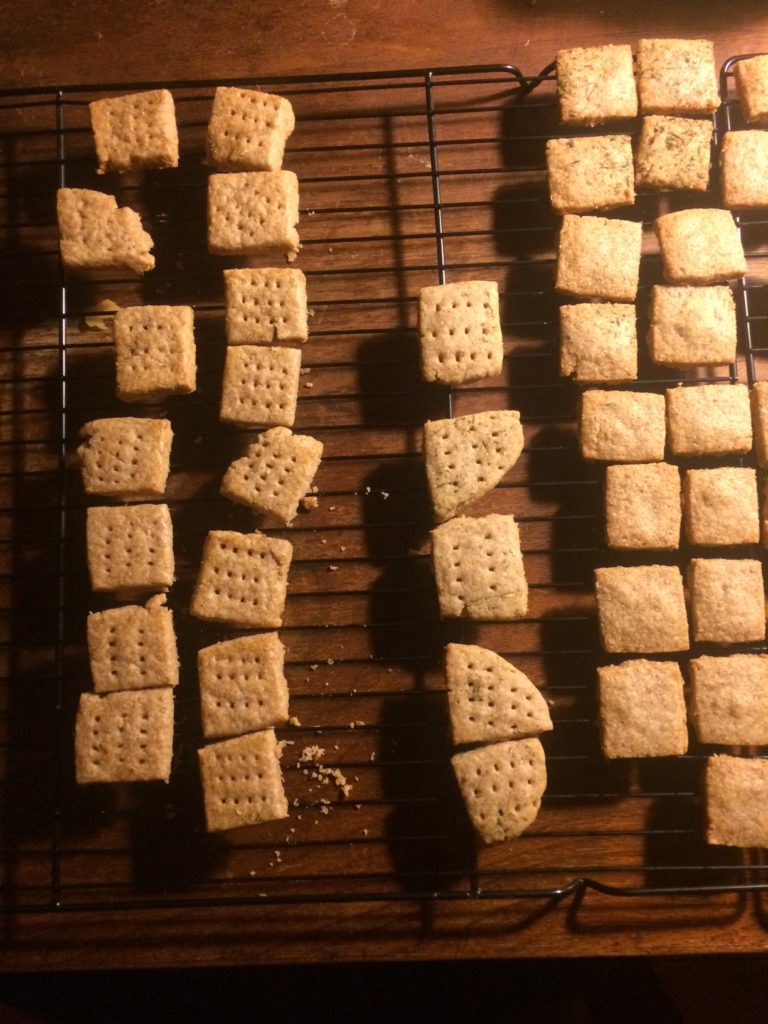

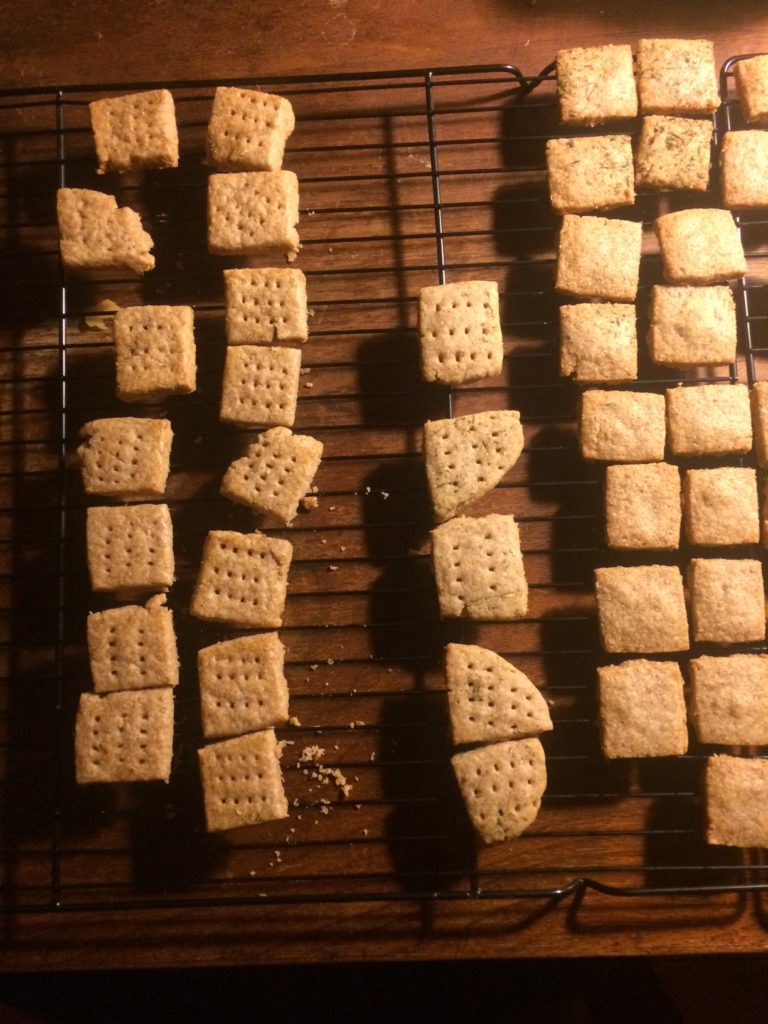

Preheat oven to 350°F. Cut into 1 x 1 inch or 2 x 2 inch squares; or cut rolls into slices ¼ inch thick. Place cookies of the same size on an ungreased sheet. Poke tops with fork tines. Bake 9 minutes for small cookies, about 12-15 minutes for larger. Let set slightly on cookie sheet, then cool on racks.

I made rye shortbreads, and whole wheat pastry shortbreads. They went down pretty well. But the BIG hit is the following one, based on Dorie Greenspan’s recipe for Cornmeal Shortbread Cookies. I chose the cornmeal-rye combo because this is the most American grain pairing, and indicative of what a lot of people ate before the wheat belts were developed. (I wrote about this in my booklet, THE PANCAKE PAPERS, essays and recipes that didn’t fit in my book.)

Spicy Cornmeal Rye Shortbread

2 sticks/8 ounces butter

1/3 cup/80 grams sugar

1 cup/4 ounces/115 g stoneground cornmeal

1 cup plus 2 tablespoons/4 ounces/ 115 g whole grain rye flour

1 cup/4 ounces/115 g whole wheat pastry flour

1 tsp salt

1 tsp ground cumin

1/2 tsp chipolte powder

1 tsp smoked paprika

Cream the butter and sugar. Mix the flours, salt and spices together in a separate bowl. Combine both together to make the dough. If it’s not stiff, add a little more pastry flour. If it is very crumbly, add a teaspoon of water, or alcohol.

Roll the dough flat between sheets of waxed paper, ¼ inch thick. Alternately, use the waxed paper wrapper from the butter to roll some dough into a round or square log that you will slice into shortbreads.

If you’d like, sprinkle some nigella seeds or pepper flakes lightly into the square. If you’ve made rolls, you can press these tasty things — or others — onto the sides. Refrigerate the dough on a cookie sheet for a couple of hours or a couple of days. OR, if you are short on time, flash in the freezer for about 20-30 minutes.

Preheat oven to 350°F. Cut into 1 x 1 inch or 2 x 2 inch squares; or cut rolls into slices ¼ inch thick. Place cookies of the same size on an ungreased sheet. Poke tops with fork tines. Bake 9 minutes for small cookies, about 12-15 minutes for larger. Let set slightly on cookie sheet, then cool on racks.

I packed up some shortbreads for Jack to bring on the train — he left for Seattle, to be with his folks and sister for Thanksgiving. I’m glad he’ll have them for nibbling as he reads.

I packed up some shortbreads for Jack to bring on the train — he left for Seattle, to be with his folks and sister for Thanksgiving. I’m glad he’ll have them for nibbling as he reads.

Hope you’ll try your hand at these for your holiday meals and gift making.

`